Demanding More from Your Sectional Matrix System

There are many challenges to restoring a tooth back to its natural shape, contour, and shade using a direct composite technique. Fortunately, advances in composite restorative material and adhesion have enabled today’s dentist to control most of the esthetic variables and create results that closely mimic its original state. However, there is still the matter of a properly established proximal contact. Proper contour, tightness, and location of the contact can be elusive and difficult to control at the time of placing the restoration. An open or loose contact can be harmful to the periodontium and can shorten the lifespan of the restoration. In addition, it can be a daily source of frustration for the patient due to food impaction. The answer to this dilemma simply lies in the selection of your matrix system. Circumferential matrices have enabled the dentist to restore multi-surface amalgam restorations for many years. However, the advent of the sectional matrix systems have provided the dentist with more control over Class II contours and placement, resulting in a more natural and functional composite restoration.

There are many challenges to restoring a tooth back to its natural shape, contour, and shade using a direct composite technique. Fortunately, advances in composite restorative material and adhesion have enabled today’s dentist to control most of the esthetic variables and create results that closely mimic its original state. However, there is still the matter of a properly established proximal contact. Proper contour, tightness, and location of the contact can be elusive and difficult to control at the time of placing the restoration. An open or loose contact can be harmful to the periodontium and can shorten the lifespan of the restoration. In addition, it can be a daily source of frustration for the patient due to food impaction. The answer to this dilemma simply lies in the selection of your matrix system. Circumferential matrices have enabled the dentist to restore multi-surface amalgam restorations for many years. However, the advent of the sectional matrix systems have provided the dentist with more control over Class II contours and placement, resulting in a more natural and functional composite restoration.

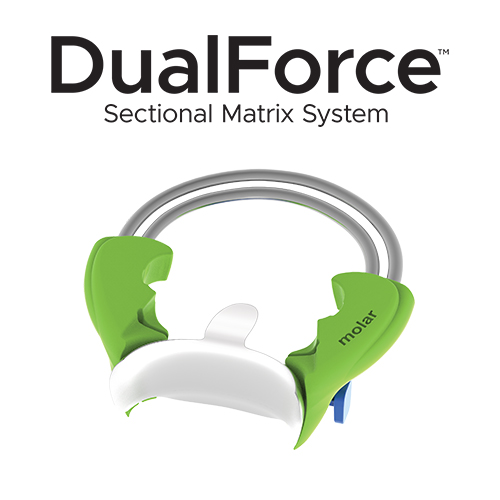

The interproximal margins of your Class II restoration may finish at varying distances from the contact area while the height of the clinical crown can differ from case to case. These factors must be considered when choosing an appropriately sized sectional matrix band. Having a selection of matrix bands of varying heights will enable you to properly fit the matrix to the depth of the proximal box. Furthermore, choosing a sectional matrix that wraps the tooth well beyond the proximal line angles, as well as is contoured both proximally and occlusally, provides the first step toward an esthetic and functional Class II composite restoration.

Once the appropriately-sized sectional matrix band is accurately in place, it is essential that it be stabilized and that the matrix band is tightly sealed against the gingival margin by a wedge. Failure to ensure this may result in excess composite flash that is difficult and time-consuming to remove. This excess may also be under-polymerized, leading to a potential void in the margin. The lowly dental wedge has undergone many transformations over its long history. From sycamore wood wedges to plastic wedges that can be cured through, their primary role has remained the same: fill the interproximal space and do its best to seal off the gingival margin with the matrix. Triangular wedges of any material have a tendency to back out of the space and inadequately seal the matrix to the tooth when they do stay in place. Plastic wedges were designed with a more anatomical shape in order to address the challenge of sealing the matrix throughout its contact with the proximal margin. However, these wedges lacked the ability to supply any separation pressure. On the other hand, larger wooden wedges could separate the teeth but lacked the ability to provide a complete seal. We need more from a wedge. Ideally, we need the wedge to physically adapt to the contour of the gingival margin with even pressure from buccal to lingual and create enough separation force to cause the interproximal space to expand temporarily and rebound upon removal. Technology has caught up to these needs and has become an integral part of the sectional matrix system.

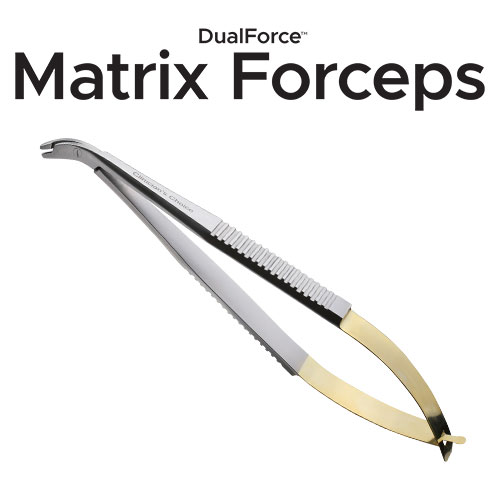

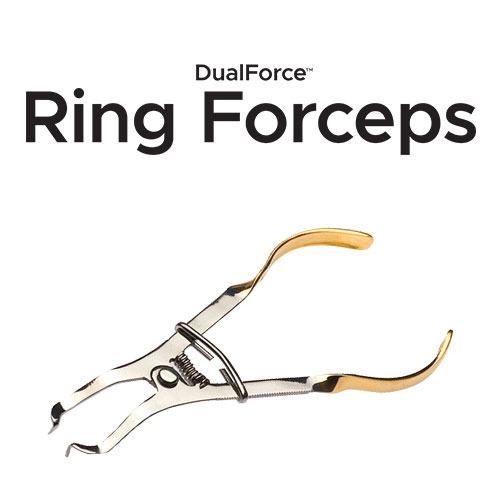

The evolution of the separating ring in today’s sectional matrix systems is the real game changer when it comes to proximal contact formation. Unfortunately, some rings require excessive hand pressure to open the ring in order to place it on the tooth. Vertical tines – intended to press the matrix firmly against the tooth – may only make a point contact with the matrix, possibly springing unexpectedly off the tooth or allowing flash to be formed from composite overflow. Separating forces of various degrees are generated in each of these systems, but can diminish over time as the metal ring fatigues.

Some rings have plastic tines or ring covers that can fracture. Both metal and plastic components of most systems become sticky with excess adhesive and composite, making cleanup tedious. Separating rings that seat parallel to the occlusal plane may not have the ability to be stacked for MO/DO/MOD applications or clear a neighboring rubber dam clamp or tooth.

The ideal separating ring is:

- Easy to place

- Engages the sectional matrix in such a way that all cavosurface margins are sealed

- Provides separation forces that are adequate and consistent

- Constructed of both metal and plastic that are resistant to fatigue/breakage and resist the sticking of composite and adhesive

- Provide adequate vision for the clinician to place and polymerize the restoration

- Available in smaller versions capable of fitting pre-molars or to provide more separating force

- Can be stacked and oriented in a manner to avoid interference with rubber dam clamps and over-erupted cusps.

A separating ring that could satisfy this exhaustive list would result in a Class II composite restoration that would be efficiently placed, would require very little marginal finishing, and would mimic the natural tooth’s proximal contour and function.

Any attempt to restore a tooth to its original form and function includes a plethora of variables. If any of these variables are not properly controlled, it can lead to a clinical disappointment or even failure. Utilizing a sectional matrix system that addresses the challenges of the proximal surface, especially the contact, is vital to achieving your clinical success.