Impression Accuracy Goes Beyond the Perfect Margin

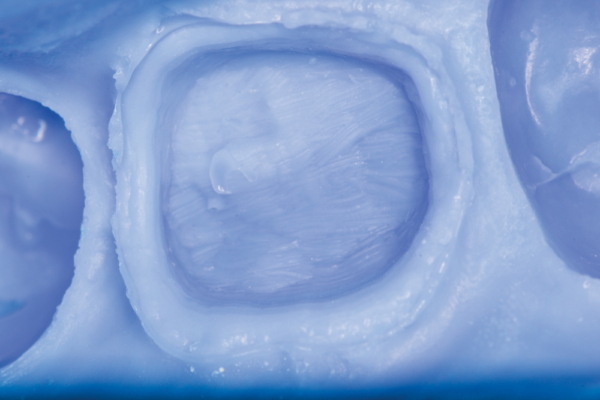

There is no doubt that precise models of the prepared and opposing arches, properly articulated and mounted, give the lab technician the greatest potential for a successful indirect restoration that satisfies the patient’s specific requirements for form, function, and esthetics. Accurate and stable final preparations are a necessity; the opposing arch impression must contain the finest detail of anatomy; articulation of the upper and lower models requires an accurate and stable bite registration that must seat within the prepared arch and opposing model without interference. This “bite registration-model” unit must then be accurately mounted in an articulator that will reflect the patient’s centric, eccentric, and protrusive movements to guide the lab technician toward the final restoration. The path that the dentist must take to provide this is strewn with challenges at almost every step.

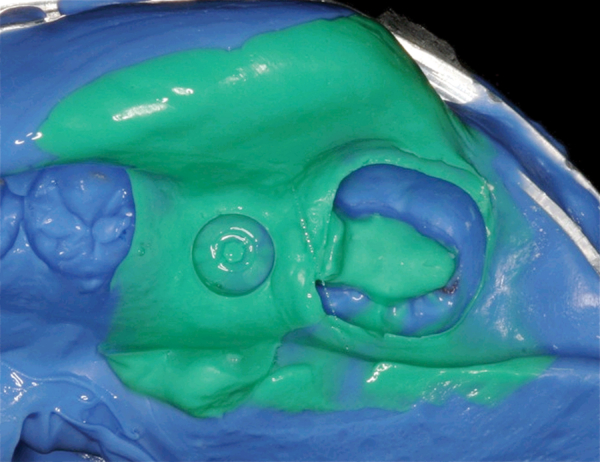

For larger, more complicated, multi-unit cases, the aforementioned technique must be adhered to without question. However, single crown or two adjacent crowns cases have been successfully restored using a dual-arch impression technique for many years. This technique provides the laboratory with a quadrant impression of the prepared arch, a bite registration, and a highly accurate quadrant impression of the opposing arch – all in one stable combined impression. Obviously, the practitioner must exercise caution as to which indirect cases are suitable to this technique. For instance, the number of units involved should not exceed two adjacent crowns, although some rare cases of small three-unit bridges may be suitable for the dual-arch impression technique. Additionally, the crown should not be on the terminal tooth of the arch as the goal is to still provide the laboratory with as much information as possible to ensure a proper fitting and functioning restoration. This includes the impact that the patient’s occlusion can have on the case.

While the dual-arch impression technique is a simplified version of the articulated full-arch tray technique, there are pitfalls to avoid in each of its steps. The incorrect choice of tray, as well as tray material and/or light body, can all have a negative impact on the final impression and consequently, the final restoration.

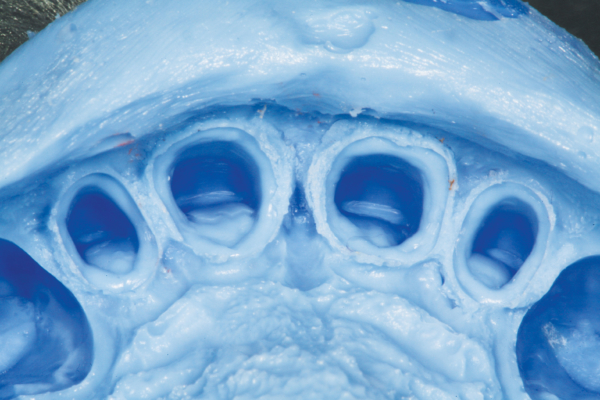

The quadrant impression tray must be wide enough, yet adaptable to fit a myriad of quadrant lengths, widths, and tooth position scenarios. As such, the adjusted tray has to be comfortable enough for the patient to endure the setting time. There can be no painful hard or soft tissue impingement that may alter the patient’s ability to occlude in the appropriate matter. The tray must also be stable throughout the impression procedure, regardless of the occlusal forces placed on it through the patient closing into the impression material, as well as during the removal of the impression from the mouth. Any distortion, no matter how slight, may result in an ill-fitting restoration requiring adjustments in order to be functional. The ideal tray will hold the tray material securely so that it does not pull away from the tray upon removal from the mouth. Tray stability throughout the impression procedure is paramount to a highly accurate final impression.

One must be careful when utilizing a plastic tray for a final dual-arch impression. Many plastic trays have a narrow occlusal table and are elastic in nature. This may lead to hard tissue interference from a tooth that is either in linguo or bucco-version. The interference will decrease the accuracy of the bite registration element of the dual-arch impression. Additionally, the mere force of the patient biting into the tray material, with or without hard or soft tissue impingement, may cause the tray to twist or flex. Upon removal from the mouth, the plastic tray will instinctively return to its original shape. This will lead to distortion of the final impression that is indiscernible to the naked eye. Only the rigidity of the set tray material may keep this from happening.

The tray material chosen for the dual-arch technique is also vital for providing the laboratory with a stable, accurate impression. Dual-arch impressions differ from full-arch impressions in that a great deal of dimensional stability of the impression depends on the rigidity or hardness of the tray material versus the metal or plastic full-arch tray. The best choice would be a tray material designed to be both as rigid as possible, yet displaying the ideal flow that does not displace the light body from the preparation. For optimal dimensional stability, ensure that the upper and lower aspects of the tray material are actually connected buccal and lingually.

The choice of light body is dependent on the particular syringing technique being used as well as its setting time. Furthermore, the setting time and the light body’s compatibility with the tray material is important to ensure a seamless interface between the two viscosities, as well as the light body’s ability to resist displacement by the tray material.

Ultimately, the success of your dual-arch impression technique will be determined at the crown insertion appointment. The degree to which you have to adjust the crown proximally, internally, and occlusally will determine how accurate and dimensionally stable your dual-arch impression is. A simple visual inspection of the impression upon removal of the mouth will not reveal any level of distortion. That will be determined by the amount of chairside adjustment required to seat and establish proper occlusion. Since chair time is a clinician’s most valuable resource, simply reviewing your dual-arch technique and materials may result in significant time savings and a superior quality restoration.